June 27 unBox White House Listening Session in Cambridge, MA

We submitted the insights of our June 27 Listening Session to the White House Conference organizing staff by their July 15, 2022 deadline. You can read our comments, identical to those in this article, as a PDF.

In May 2022, President Biden announced that this September will mark a historic event: a White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health—the first of its kind in 50 years. The goal of the conference is to kickstart a national strategy that will help the US “end hunger and increase healthy eating and physical activity by 2030, so that fewer Americans experience diet-related diseases like diabetes, obesity, and hypertension.” The previous White House Conference dedicated to hunger and nutrition hosted in 1969 recommended 1,800 actions, and vastly expanded SNAP and school lunch, started the School Breakfast Program and WIC, and raised awareness around hunger. The White House has repeatedly expressed its commitment to engaging a diverse spectrum of stakeholders in the convening of this conference and in the implementation of its recommendations. Part of this engagement has involved the White House’s solicitation of organizations nationwide to convene their communities in White House Conference Listening Sessions. By organizing, rigorously documenting, and submitting feedback from these listening sessions, organizations want to ensure the voices of the communities they represent are heard. In particular, the White House wants to hear from individuals with lived experiences of hunger and diet-related illness about how US programs and food policy could better support them.

unBox organized two White House Conference Listening Sessions. On June 27, we hosted our first dialogue, “Hungry for a Just Food System”, at a cooperative living house called pika in Cambridge, Massachusetts in which a couple of the event organizers live. (You can read the insights of our second, virtual dialogue here.) We organized this event because the voices of young people are consistently underrepresented in conversations about our country’s future. We have inherited this unjust and unsustainable food system. We need a place at the table in conversations to transform it today—because it will impact how we put food on the table for decades.

We organized this event because the voices of young people are consistently underrepresented in conversations about our country’s future. We have inherited this unjust and unsustainable food system. We need a place at the table in conversations to transform it today—because it will impact how we put food on the table for decades.

The conversation brought together 14 young people with diverse experiences of US food systems, and unique visions for how they could be transformed to reflect young peoples’ future visions and ideas for a more just, sustainable food system for all Americans. We are incredibly grateful for the the partnership and support of the Food Systems for the Future Good Food Dialogues platform. Their website helped provide an invaluable means of promoting our event, and helped us document and organize our feedback into a document to share with the White House Conference organizers. We are also very thankful for Guillaume Bouchard for taking wonderful photos. All event participants provided consent for their photos to be taken and shared, and for their anonymous and de-identified feedback to be recorded and shared.

In this article, we document:

the food systems issues that participants believed were most important

specific policy proposals

participant stories and experiences

areas of divergence

reflections on organizing the dialogue

MOST IMPORTANT ISSUES

The major focus of our Dialogue was elevating youth voices, and speaking up about the US food systems issues we care most about. Because our generation has inherited this system, and because we now bear the responsibility of ensuring it can nourish and sustain our bodies, the planet, and future generations, it is critical that the concerns and ideas of youth be centered in future US food policy.

The main US food systems issues that our Dialogue participants want the White House to address are:

1. Expanding healthy, affordable food access for low-income communities, immigrants, unhoused people, and other minoritized groups; for rural communities; and for college students, because fueling low-income and first-generation students through college is essential for reducing income inequality and increasing economic mobility. Working tirelessly in school, extracurriculars, and part-time work, while also worrying about how to afford food, forces students to make impossible choices between their basic needs and their education.

2. Moving to a sustainable, circular food economy that connects Americans more deeply to land, rather than estranging them it; supports those who try to grow their own food, at a small or even micro scale; does not exacerbate climate change, and even helps mitigate it; does not overconsume natural resources; is environmentally just; curtails the impending threat of antimicrobial resistance; transitions to sustainable, regenerative agriculture; uplifts traditional ecological knowledge, particularly those of Native American land stewards; reduces food waste; invests in urban farming; and reduces industrial animal agriculture in favor of conservation grazing and regenerative livestock and dairy.

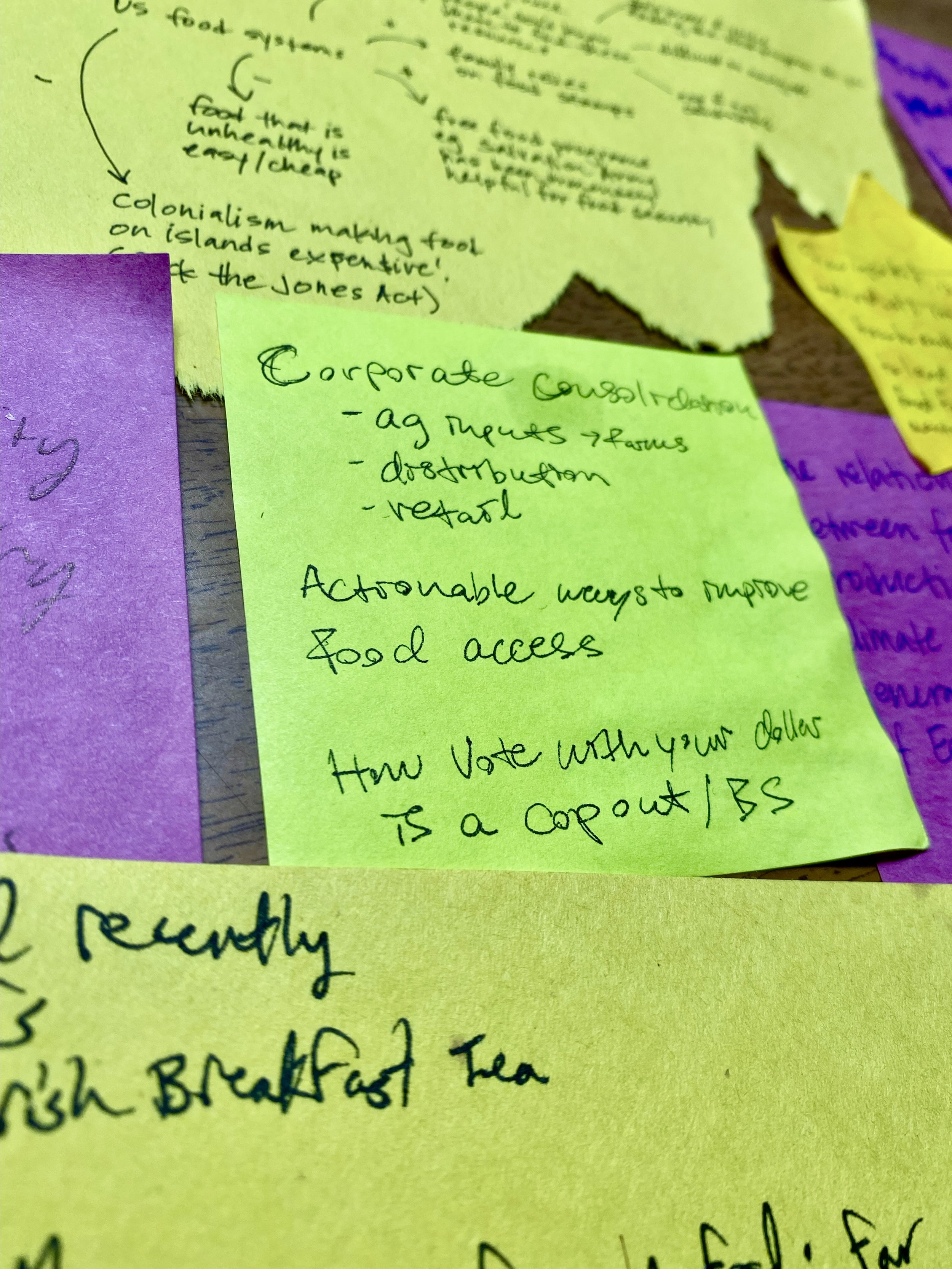

3. Advancing economic justice and supporting small business entrepreneurship by curtailing corporate consolidation amongst large farms, distributors, and retail companies; reducing poverty; avoiding re-perpetuating colonialism; and eliminating barriers for and supporting Black and Indigenous and other farmers of color

POLICY PROPOSALS

Our Dialogue participants proposed specific policy recommendations derived from members' own lived experience with food and financial insecurity, members' work on local, state, or national food systems policy and research, and other diverse experiences interacting with the food system as eaters, cookers, growers, activists, and thinkers:

1. Involve youth. The White House must actively involve young people in policy development and implementation. We gathered at this Dialogue because we were frustrated with feeling unheard and unrepresented; we are excited at this rare opportunity to be heard amongst the halls of power. The White House should proactively engage BIPOC, LGBTQ+, immigrant, and disabled youth, farmers and rural youth, and youth who receive or whose families receive SNAP, WIC, free or reduced price school meals. The WH can do this by A) working with USDA to create regional food systems visioning committees on which young people serve, B) expanding internship opportunities for young people to work in the White House and USDA before, during, and after college, C) increasing AmeriCorps VISTA program pay, D) helping schools design civic engagement curricula covering how to pre-register to vote, research legislation, contact their state and federal representatives, and provide public comment, and E) supporting campus groups engaging their communities on food systems issues.

2. Increase SNAP. Today, the US government's most powerful tool for helping prevent Americans from falling into food insecurity is increasing SNAP.

3. End student food insecurity. The White House must act creatively, urgently, and in partnership with student-led groups to end campus hunger for good. Education is the most important lever for equalizing opportunity and economic mobility. Students who must stretch their mental bandwidth and financial budgets to afford basic survival needs do not have the same chance at educational success as students who don't carry that burden. Eliminate student SNAP restrictions.

4. End consolidation and monopolization at every level of the food system, to make way for innovation and entrepreneurship. Massive mono-crop farms, big meat giants, and grocery retail mega-corporations get bigger by the year and swallow up competition. The WH should work with the FTC to regulate and limit monopolies and restore competition. Support small farmers, grocery retailer entrepreneurs, and grocery cooperatives.

5. Support Americans' reconnection with land. Eliminate barriers for Black and Indigenous and other farmers of color. Support urban farming initiatives, particularly BIPOC-led initiatives incorporating food justice experiential education for youth. Fund "Double Up" SNAP incentives at farmers markets. Repeal the Jones Act to reduce food insecurity in Hawai'i and the US territories and invest in sustainable, regenerative agriculture on US islands.

PARTICIPANT STORIES AND EXPERIENCES

THE SOCIAL SAFETY NET

We need a stronger social safety net. One dialogue participant, a first-generation immigrant and student leader in their campus's first-generation low-income (FLI) organization, shared, "I grew up in Vegas. The food stamps program has been vital for my family. Having an extra couple hundred dollars was really helpful. The Salvation Army would also have food giveaway days, and we would pick up five big packets."

“I grew up in Vegas. The food stamps program has been vital for my family. Having an extra couple hundred dollars was really helpful. The Salvation Army would also have food giveaway days, and we would pick up five big packets.”

Another participant, a recent college graduate, explained, “It's difficult to navigate what the best program is. There are no centralized resources to accessing the programs that exist, and those who can’t and them are those who need them the most. I’m from Guam. Its a modern-day colony; I’ve seen how colonialism affects our access to food. It's an isolated and small island. Due to certain naval laws, it's expensive to ship food to Guam. The food on the military bases is cheaper and fresher. This upholds modern-day imperialism. But there's also abundance. In mango season, for example, we’re overflowing. My friends will spear fish; we’re abundant in those ways." This participant went on to describe how the Jones Act articifially and prohibitively raises prices in US territories and should be repealed.

“I’m from Guam. Its a modern-day colony; I’ve seen how colonialism affects our access to food.”

Another participant, a nonbinary student from the Midwest, reected on income-based nutritional disparities: "In high school, many students were getting free or reduced price lunch, and they were less quality than the ones you’d pay for."

Dialogue participants convened around the shared ideas that a stronger social safety net boosts food security, reduces poverty, and helps equalize opportunity.

FOOD AS COMMUNITY-BUILDING

Food brings people together. The US food system should empower, not decenter, that truth. Today, food insecurity, poverty, environmental degradation, and monopolism robs the food system and everyone who participates in it of their dignity. Instead, young people want to experience food as "joy", "a vehicle for health", and "a means of communication, in a way that language fails." When we circled the room, asking "who is one person who changed the way you think about food?", people shared about learning intergenerational knowledge through cooking with grandparents, and reflections on living in a coop in which everyone cooks for one another. As one participant said, "Community makes it taste better." Sometimes eating well and nourish our bodies feels like "an act of rebellion" against the current food system. Young people long for a food system that helps them connect with food, land, and other people with dignity.

CONNECTION TO LAND AND TO GROWERS

Instead of 24/7 access to over-processed fast food, we want access to farm-fresh produce and relationships with the people who grew it.

One current student reflected on her hometown, which "had a centrally-located farmers market. It was nice going every week and seeing people from the community gathering there."

Another participant reflected on “the joy of Haymarket", a large, 300-year-old open-air market in Boston in which farmers sell produce they couldn't sell to grocery stores, at very affordable prices. They compared the Haymarket experience to "the sadness of growing up in a place where there were fewer connections to local farms".

Sharing a different perspective, another student explained, “Coming to America, in the past two years, it's markedly easier to access fast food. You can feel the fast food regime. I don't know if it was Canada, or growing up poor in the countryside. We had to make all out own food, so of course it isn’t processed."

“I am from Virginia, many folks are growers. People grew up on farms and appreciate food grown locally. But then people left the farms.”

Another recent graduate and Consumer Citizen Representative with Equal Exchange, an organization supporting farmer co-operatives and Fair Trade, shared, "I am from Virginia, many folks are growers. People grew up on farms and appreciate food grown locally. But then people left the farms. Now I'm in Ohio, a part of the country where the most food grown locally is consumed locally."

Other students spoke about inspiring initiatives working to close the loop between farms, grocery stores, dinner plates, and food waste. There are campus listservers which spread the word about safe, plentiful dumpster-diving opportunities. Daily Table is a nearby nonprofit grocery store. "Too Good to Go" is a new app connecting stores with surplus produce with those seeking food. Food Not Bombs runs local food security programs and food justice education workshops. Reflecting on the ways our disjointed system disconnects people from the sources of their food, while generating waste and also leaving millions food insecure, one student summarized: “Ideally there would be better systems for this.”

CREATIVITY AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP OVER CONSOLIDATION AND MONOPOLIZATION

The US food economy should be fair and competitive. Corporate monopolies reduce innovation and opportunity. A major issue participants identified was "anti-trust", arguing, "Maybe companies shouldn’t gobble up one another, and maybe that doesn’t happen naturally. There’s Tyson and Purdue dividing and conquering regions of the US.... Farmers need a price floor to keep farmers employed, otherwise big farms scoop them up."

Participants also spoke to the inspiring rising tide of unionization at companies like Starbucks and Amazon, and wanted to see an end to corporate union-busting.

One student from upstate New York shared about proudly shopping at ShopRite, a member of Wakefern, the country's largest retailer-owned grocery cooperative.

One student summed up the conversation by explaining, "Voting with your dollar is a cop-out." To help enact real systems- wide change, we need to vote with our votes to elect politicians that refuse to let corporate interests and campaign funding sway their ideology, that believe in competitiveness, fairness, anti-trust, and small business entrepreneurship, and that listen to their constituents over companies.

AREAS OF DIVERGENCE

Two key areas of divergence emerged during our dialogue. First, participants had different views about which part of the food system supply chain was most impactful to influence to increase sustainability, reduce food insecurity, increase economic fairness, and achieve food justice. Some focused on nutritional benefits programs, retail grocery store prices, farmers markets, and other demand-side interventions. Others focused on subsidies, corporate agriculture, and food distributions networks. While each of us thought that action at specific points in the supply chain may be more or less impactful than other points, we all agreed that holistic food systems transformation must happen at every level. Part of the challenge facing food systems reform today is the siloing of various stakeholders into niches of the supply chain, when in fact, the whole chain is connected in a large circle.

The second area of divergence regarded which level of impact would be most change-making: local, city, state, federal, or international action. Some participants argued that all change is local, while others spoke to the power of massively-funded federal programs. Ultimately, all agreed that coordinated, organized action at all levels is necessary to transform the food system. Some people, however, might be best equipped to act at certain levels for greatest impact, so all should reflect on their strengths, positionality, and skillsets when choosing the niche and community in which to rally.

REFLECTIONS ON THE ORGANIZING PROCESS

HOW DID YOU ORGANIZE THE DIALOGUE SO THAT THE PRINCIPLES WERE INCORPORATED, REINFORCED AND ENHANCED?

Prior to even committing to hosting this Dialogue, my co-organizers and I researched the White House Conference values and goals and those of the Good Food Dialogues network. We were impressed and excited to explore the WH Conference's demonstrated commitment to engaging diverse stakeholders, inviting transformative ideas across many sectors of the food system, and following through on actionable policy. Then, in reading the Good Food Dialogue's Principles of Engagement, which aligned deeply with unBox's organizing philosophy, we decided to move forward in hosting a Dialogue. Our process for planning, intentionally designing, publicizing, then hosting the event incorporated the Principles of Engagement, as well as many of our own values around facilitation and organizing: First, unBox always acts with urgency. This is why, when we saw the opportunity to host a Dialogue, we took stock of our already very stretched capacity amongst unBox team members working full time jobs and decided to *make the time* needed to do this and do it well. Secondly, respect is central to everything unBox does. Before we are co-organizers and activists, we are a supportive and safe community of friends. Respecting one another's opinions, personhoods, and identities enables us to do the work we want to do. Thirdly, we invite and elevate the perspectives of diverse stakeholder groups because we comprise diverse perspectives. Inviting multiple perspectives and backgrounds is not tangential to our work; it IS our work. Fourth, we wanted this gathering to help bring attention to the leadership of other organizations creating a more just, sustainable US food system. Participants pointed to examples of nonprofits and initiatives they've seen or worked with, transforming systems for good. Fifth, building trust was a central goal: we wanted the Dialogue to feel welcoming, safe, and fun. In order for people to vulnerably share stories from their lived experience, or venture to offer ideas on a topic they are new to from a policy or research point of view, trust was essential.

HOW DID YOUR DIALOGUE REFLECT SPECIFIC ASPECTS OF THE PRINCIPLES?

Our Dialogue reected urgency because it was held days after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and millions of people across the country felt as if their bodies were under attack. This unprecedented, unimaginable, and for many, life- changing ruling forced all of us to confront the profound ways that policy impacts our lives, the necessity to organize people- power, and the future consequences of inaction. In our publicity of the event and during the Dialogue, we centered this urgency and discussed the explicit link between legislation that takes away the right to choice by people with uteruses, to the right to healthy, affordable food for those living in food apartheids. Both issues represent systemic inequalities that hurt low- income people, people of color, immigrants, people with disabilities, and queer people the most. This juxtaposition heightened the urgency and intersectionality of the discussion. Respect manifested in our Dialogue in the ways that participants thoughtfully listened to and built upon one another's contributions, referencing one another's comments throughout the Dialogue and expanding on them. Our gathering at pika convened young people with a broad range of insight, including people with lived experience on SNAP, biotechnologists, rst-generation immigrants, researchers of food systems, fermentation experts, an employee of a farmer coop, farm volunteers, a resident of a US territory, and more. In discussing case studies of food systems successes we can scale and aspire to, people alluded to inspiring examples from their lives: people spoke of family members who taught them how to connect with food and land through cooking, organizations doing direct service and mutual aid in Boston, and grocery coops across the county. Participants built trust with one another by thoughtfully and patiently listening to everyone else, and snapping or nodding along in armation. We enjoyed snacks together, laughed, and had space for storytelling, all of which built trust while also building community.

DO YOU HAVE ADVICE FOR OTHER DIALOGUE CONVENORS ABOUT APPRECIATING THE PRINCIPLES OF ENGAGEMENT?

My co-organizers and I agreed that respect, trust, and diversity were the three most important values to center in organizing a Dialogue. When those intentions are present and thoughtfully enacted, all other goals will fall into place. Strategies that we deemed successful in organizing this Dialogue around those principles included: - Inviting our friends. We reached out to housemates, new friends, friends of friends, and more encouraging them to come, share, and learn. Having some participants present who already know one another created easy-going familiarity, and the impression that this was a gathering of people who like spending time with each other, regardless of the issue at hand. - We had snacks at the event, which was like a small token of appreciation for folks' time, and always makes the mood for fun and friendly. - We attempted to design a range of questions that everyone - regardless of their confidence in their "food systems expertise" - could answer. All could contribute to the question: "Name one person in your life who has impacted the way you buy, grow, cook, eat, or think about food." And, many could also contribute at a deeper level to suggest specific policy suggestions for reforming US foos systems. Allowing space for every level of confidence and experience along that spectrum invited everyone to participate. - We publicized the event widely and urgently. We hosted the event in the coop some of us live in, so we announced the event at successive house meetings, messaged the house group chat about it, blasted and emailed to the list of current housemates and alumni, posted on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram, and, of course, on the GFD platform. - We compensated a meeting attendee to be our photographer.

Thank you for reading the collective reflections documented during our June 27, 2022 White House Conference Listening Session. unBox also hosted a second, virtual Listening Session on July 11, 2022. You can explore our notes here.